In Gorochivske village, life is slow. On a gravel road covered in very intense February snow, Vasil Mujisevic struggles with his bike. The red metal drill is held on it. Vasil Mojseyevich was fishing.

But fish are crafty. There was no pacifier this day either.

Vasil Mugcjevic is one of very few village residents who changed his name five years ago.

Previously, the village was called Petrivske and the street across the village was called Petrivska, in honor of the People’s Commissar, says Vasil Mojsejevich.

People’s Commissar Grigory Petrovsky, who was responsible for implementing Stalin’s policies in the Ukrainian Soviet Republic.

But what now?

Now, Vasil Mojseyevich says, the name of Gorochivske Village has been changed after a stream flowing through the community.

This disconnect, for a gay man who lived for 77 years, yes it is pure snow in the ears of an elderly person.

The Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine made the decision to rename the village of Petrifsky in February five years ago. On the same day, the names of more than 170 other villages and communities across Ukraine were changed. In this way, many of the villages of Lenin, Karl Marx, October and the Red Army disappeared from the map.

In Kiev, at the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance, the head of the National Institute of Remembrance, Anton Drobovich, says that since the start of the decommissioning campaign, tens of thousands of names have been changed. He says it twice. Tens of thousands.

The National Remembrance Institute was founded in 2006 as part of restoring what Ukraine had denied for 70 years due to Soviet rule. The memory of an individual’s national history as well as the memory and truth of the crimes committed during the communist dictatorship. Anton Drobowitz says keeping names that remind us of that time would be an insult to the victims.

Anton Drobovich is well aware of this This is far from all Ukrainians supporting his work. Many want to keep the names they are used to. Before each name change, open dialogue forums are held where residents can express themselves and experts, such as historians and ethnologists, are invited. Because in reality, says Anton Drobowitz, all these villages, streets and cities that now got new names were called something else before the creation of the Soviet Union.

During the twentieth century, many names were changed by force in honor of some Communist positions, says Anton Drobowitz.

Some metro stations from the center of Kiev run the Moscow Bulletin, or Stepan Bandera Bulletin. A name dispute is currently underway in court. Ukraine’s decommissioning campaign has not been without controversy and the National Remembrance Institute has come under criticism.

In 2019, the former president, Volodymyr Vyatruvic, was fired. While working for Radical Secession, he was accused of honoring other controversial forces in Ukrainian history, such as Stepan Bandera, a leader of national liberties and independence fighters before World War II who also collaborated with the Nazis.

During the revolution in Ukraine in 2013 and 2014, which was followed by Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the war in eastern Ukraine, Stepan Bandera was hailed as a hero. And now the battle is over whether or not Moscow’s horizon in Kiev should bear his name.

At a bus stop some distance from the road, photographer Volodymyr Dubetsky says he may lean towards Stepan Bandera and that the road should not under any circumstances bear the name of the country’s capital, Russia, which Ukraine is seen as an attacking country. .

Next to one bus stop A large book market and there, under the hood, Kyivbon says that, on the contrary, she prefers to see that the road keeps its old name, the Moscow Bulletin.

– I grew up in the Soviet Union, the Soviet Union. I carry craving. I was fine at the time. When I studied, got a job, I felt safe for tomorrow. On the other hand, my children’s future is very uncertain, she says.

On a small street in the center of Kiev is the Ministry of Culture of Ukraine, and there I ask the same question to the Minister of Culture and Information Oleksandr Tkachenko. Moscow prospects or Stepan Bender’s expectations?

Did you get the choice, or either, says Oleksandr Tkachenko, but he adds that it is very important to discuss such issues now openly and freely. He says we must reclaim our Ukrainian identity.

– If we do not define ourselves as Ukrainians, we will continue to be a Soviet people with the values that come with it. We should create our own values, Oleksandr Tkachenko says, and he mentions concepts like freedom and dignity.

We should not dismiss everything about Soviet history, he says. The scientific progress that has been made, as part of the architecture going back to that time, must be preserved. But it is not what represents persecution.

He himself mentions the name that distinguished many cities, villages, streets and squares in Ukraine: the name of the People’s Commissar, Grigory Petrovsky, who was responsible for implementing Stalin’s policy in the Ukrainian Soviet Republic. It was he who gave the name to the village of Petrivsky, now Gorushevsky.

The dogs are barking on the other side Fence on the road where Oleksandr lives.

Oleksandr carefully opens the gate and exits. He has lived here since 1962, the year he was born.

The name Petrovsky, or Petrovskogy in Russian, has nothing to do with this Communist, he says. It is just that here in the village there have always been many people living with that name, Pietro.

When someone asks me, I say that I live in the village of Petrovskogy, everyone knows this name, says Oleksandr.

“Falls down a lot. Internet fanatic. Proud analyst. Creator. Wannabe music lover. Introvert. Tv aficionado.”

More Stories

More than 100 Republicans rule: Trump is unfit | World

Botkyrka Municipality suspends its directors after high-profile trip to New York

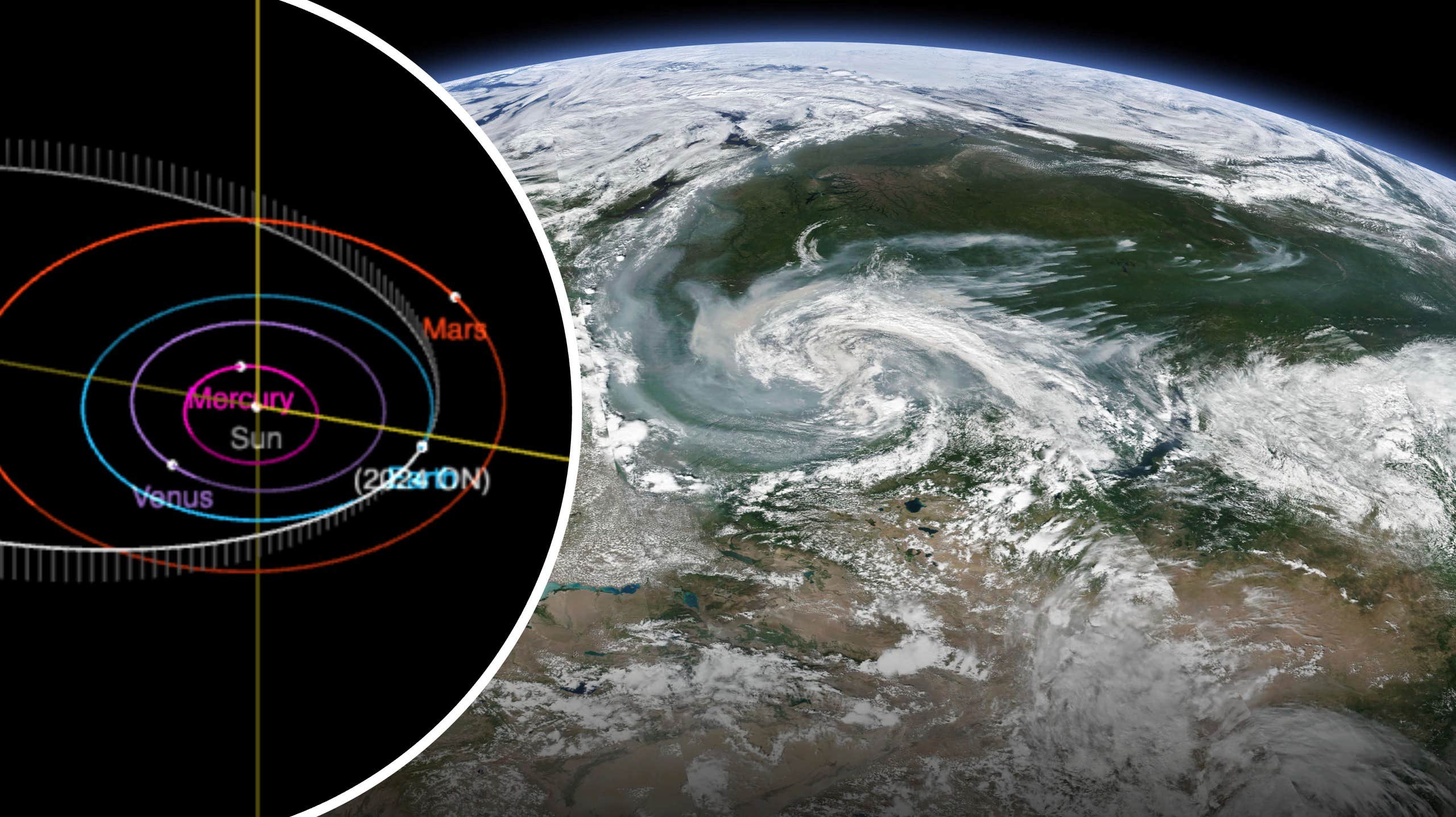

Huge asteroid approaching Earth | World